We love pirates. Their swashbuckling adventures, obsession with treasure, and whacky accents capture our imagination and make us long for the sea (even if open waters are terrifying). The fact of the matter is, however, that most of what we think we know about pirates comes from Hollywood, and like with the samurais, they rarely, if ever, get this shit right.

Legally speaking, a pirate was someone who robbed and murdered a body of water. The body of water was non-specific. There are accounts of river pirates, so we know they weren’t just terrorizing the oceans. Also, this wasn’t a one-size-fits-all definition either, as the High Admiralty of the British Empire determined who qualified as a pirate.

Things get more complicated when the term privateer enters the picture. Simply put, privateers were also robbing and murdering in open waters, but they were doing so under a contract called the letter of marque. The letter of marque was a license for certain ships to serve as corsairs on behalf of a government, capturing and robbing enemy ships. Under this license, they could keep 80% of their loot and could kill without facing government retribution. They were, essentially, pirates but pirates under legal contract with the government, and doesn’t that make all the difference?

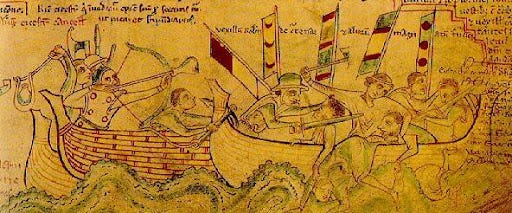

Now, pirates have been around forever. There are reports of pirate ships in Ancient Greece and Rome robbing merchant ships and generally being a nuisance. Interestingly, perceptions of pirates differed greatly depending on the region. Some viewed pirates as brave and heroic, while others thought they were the worst. But they only became super notorious in what some historians call the Golden Age of Piracy (mid-17th to early 18th century). Why is it called the golden age? One, because for the first time, we see pirates being pirates for no one but themselves. Finally, pirates match their legal definition and are not hiding behind government contracts. Second, we never see such a large band of organized pirates again after the first quarter of the 18th century.

This begs the question, who became a pirate and why? The answer is surprisingly simple–beleaguered naval or merchant sailors, the marginalized (slaves or former slaves), and people looking to make a quick profit. However, it is imperative to refrain from viewing pirate ships as some utopian society where everyone is welcome. Just because they were breaking the law didn’t mean they didn’t agree with the widespread sentiments dominant at the time. The same goes for stories about queer pirates. It’s necessary to remember that the concept of homosexuality as it exists today is completely different from how same-sex relationships were viewed at the time. Yes, there probably were queer pirates, but there is no evidence to suggest that it was an open secret and everyone was cool with it. The Matelotage contract is often cited as an example of a civil union between men on pirate ships. Still, most historians are skeptical to label it as anything other than an economic contract between two sailors to safeguard their assets. I think it could go either way. I’m sure that while many used it platonically, for some it might have been a source of validation for their same-sex partnership. And I’ll leave it at that since I was neither alive nor a pirate living in those times.

Speaking of myself, were women even allowed on pirate ships? Most of the time, no. Sailors were a superstitious lot, and women were historically considered bad luck, so most either played secondary roles or cross-dressed to get aboard pirate ships. There are, however, some examples of female pirates. Anne Bonny and Mary Reed, who sailed Captain Jack Rackam, are two of the most well-known. However, my favourite is Zheng Yi Sao, who married a pirate and took over his confederation when he died. Technically, she co-ruled with her adopted son (who she later married, but let’s ignore that), but she was the brains of the operation. Zheng Yi Sao had anywhere between 40,000-60,000 pirates under her command. At one point, she was so powerful the Chinese government had to pay her to avoid being attacked by her ships. She had a strong code of conduct for her men, especially about women. If a sailor under command cheated on his spouse, he would be executed. If he slept with a woman, he would be compelled (aka forced) to marry her. She was not messing around. And she’s one of the few pirates who got to retire and live for a long time afterward. That’s awesome!

Of course, not every pirate ship had codes as strong as Zheng Yi Sao’s, but they all had codes nonetheless. These rules were essential to maintain law and order (as ironic as that might sound) aboard these pirate ships. Some of the basic rules are as follows:

Equitable distribution of wages depending on their role.

Weapons had to be clean and well-maintained.

Injuries and amputations had to be compensated.

No usage of guns in the hold– to prevent fire or injury.

Banning of gambling and even alcohol consumption aboard the ship.

The punishments for rule-breaking, killing a fellow sailor, or stealing were decided unanimously by the crew. There is no evidence of sailors being made to walk the plank. So, let us collectively lay that concept to rest. The punishments mostly ranged from whipping to flogging to keelhauling, with the most extreme punishment being marooning. Pirates of the Caribbean got that right! I am as surprised as you are.

All this to say, pirates as we know them have been revised and romanticized beyond belief. But, for once, I’m inclined to let fictional pirates do their thing.

PS: